Houston Under Water

A friend asked how much of Houston is experiencing flooding, so I thought a post might be warranted.

First, let me say that I am fortunate enough to have been relatively untouched by Hurricane Harvey. That’s partly because we did our research before buying a house here and partly because we are the direct beneficiaries of a $120 million flood abatement project along White Oak bayou–completed just as we moved here in 2004, paid for and coordinated by a Federal program that Mr. Trump has asked Congress to eliminate, and additionally, by deep neighborhood lakes that have inadvertently acted as flood abatement since our neighborhood was built in the 1990s. Largely, it’s because we got lucky, and at the point Saturday when the White Oak was at its highest, we caught a break–a six hour respite as the heaviest band of rain passed over to the east, giving our part of town a chance to recover. Others were not so lucky.

This information is condensed from government sources and the Washington Post, which has done an excellent job covering the storm.

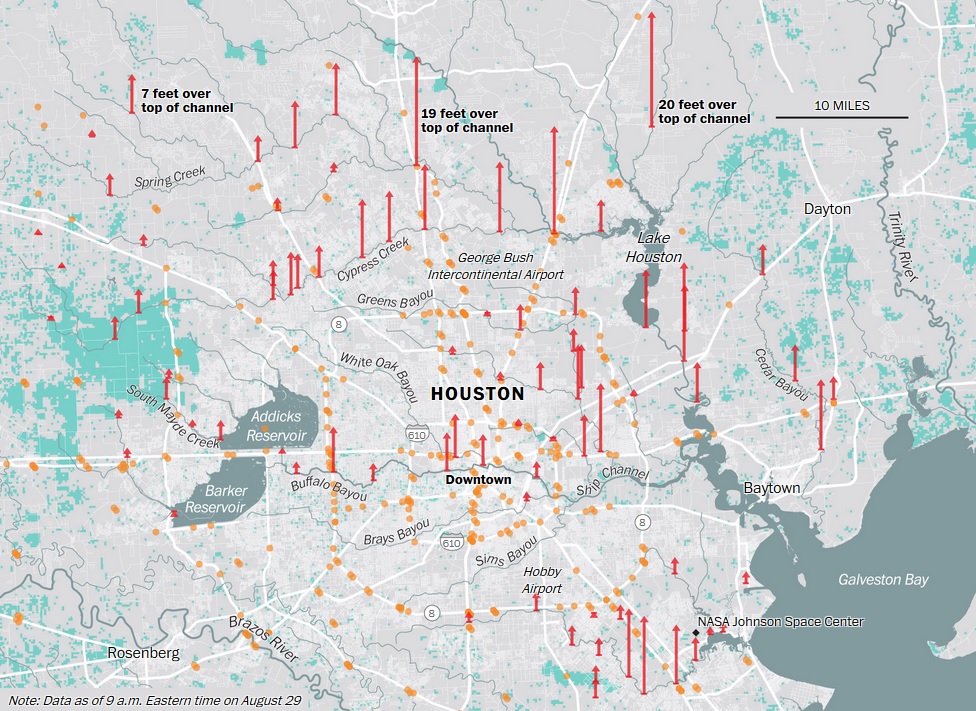

The average annual rainfall in Houston is officially 59.5 inches. Since Friday, all parts of the city have received between 32 and 52.5 inches. The 52.5 inches is a new record for the continental US, and may be low, as the sensor station on Cedar Bayou failed at that point. That’s a lot of rain, over 9 trillion gallons, over 8 cubic miles of water.

Houston rainfall cumulative annual total (dark), cumulative annual record (light), and Harvey(blue).

The immediate impact of this was the utter shutdown of the city, from Tomball in the Northwest, to Galveston Bay in the southeast. The city was founded at the confluence of the White Oak and Buffalo Bayous. Roads, then interstate highways, grew up around them. It’s alarming to many, but actually quite logical, that the major surface roads that tie the city together now form part of the normal floodplain for these waterways. We’re used to it. If you work downtown and a storm rolls in, you go home early or risk getting stuck. That’s just Houston.

This is different. Service roads and underpasses all over the city flooded simultaneously. Pumps were overwhelmed. Both airports had to be shut down. Retaining walls collapsed into the Sam Houston Tollway, one of three loops that normally keep traffic flowing around the city even in times of crisis. Miles of these loops and the interstates and feeders that connect them went under water. The Addicks and Barker reservoirs, large flood control structures on the west side that protect downtown from catastrophic floods during hurricanes both filled to the top for the first time in history.

West Sam Houston Tollway @ Main

Now the city is full of water, not because any levees broke (they didn’t) or because any government official screwed up failed to act (one can quibble, but both preparedness and response have been pretty good by normal American government standards). It just is what it is, and now the water–all eight cubic miles of it–has to make its way to the gulf.

So how much of the city is flooded? About 30 percent, including some of the city’s poorest, most densely populated areas. That’s 30 percent of a metropolitan area of 5.6 million people. There is currently no way to know what percentage of homes are actually flooded, or what percentage of those have more than a few inches.

That kind of detail makes a big difference. A little water in the front door, and you just replace the moldings. A few inches, and you might have to replace the lower part of the drywall. More than a couple of feet, and you may loose most of your personal property, in addition to having to gut and remodel. Over the next few days, the water will recede, except for certain areas like those around the reservoirs who officials say can expect to remain flooded until October. Yes, that’s right. It will take up to two months to draw the flood control structures back down to normal levels. It could be worse. At least it’s fresh water. And let us not forget, Rockport, to the South, was devastated. At least Houston’s homes and businesses are just wet, not destroyed.

How bad off is Houston? Time will tell.

Meanwhile, Houstonians and our neighbors from across the state and across the nation are coming together in a way that must give hope to all but the most hardened, cynical heart.

As I write this, various agencies and organizations have set up well over 22 shelters, including the GRB Convention Center, the Toyota Center, and NRG Stadium, where over 10,000 evacuees were housed as of last night, as first responders, the #CajunNavy, and a Dunkirk style flotilla of good Samaritans continue to bring people in. Some of these people will be renters and the ill prepared, who simply didn’t feel comfortable waiting out the flood. Many, of course, and those who need a little help under the best of times. Some–and unknowable percentage at this point–will be homeowners who didn’t or couldn’t get insurance, and whose homes are submerged to the rafters. Last night, the news interviews a guy from Austin who drove here to help–and stopped to buy a boat along the way. Another guy described the ad-hoc cloud network by which the “Cajun Navy” dispatches rescuers. A third told of water do deep, he’d pass a deer taking refuge on a rooftop.

When my neighborhood flooded, some people only had a foot of water in their houses, but it’s like you said, they had to strip down to the studs, remove all the flooring, and replace all the furniture. It’s expensive, time-consuming, and you haven’t even touched on the SMELL yet.

I sympathize so much, because this is a disaster that will keep on disastering for months to come. ::hugs::