QWERTY is Good Enough

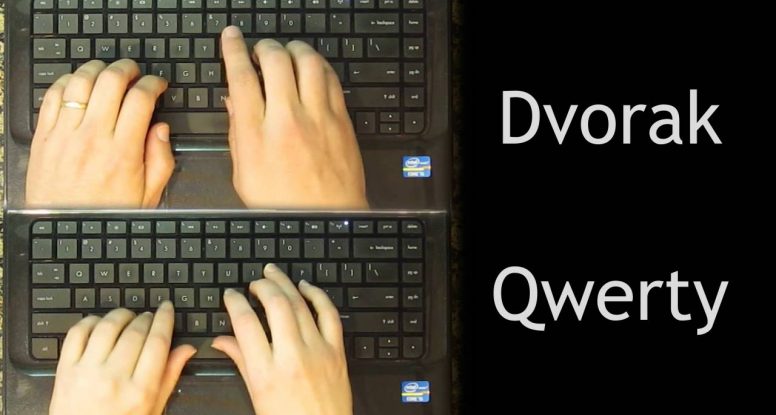

The QWERTY keyboard layout, the defacto standard derived from the Sholes layout popularized by Remington in the early 20th century, has a bad rap. It’s generally seen as either a failure of market forces or a failure of regulatory oversight, depending on your political bent. After all, Sholes designed his keyboard to prevent the jamming of keys in an antique mechanical typewriter, while Dvorak set out to rationally engineer a keyboard optimized for high-speed typing. Such a keyboard is obviously superior, and it’s only the inertia of the market that has kept the world from reforming.

There’s only one problem. It just isn’t true.

Oh, Sholes did design his layout to prevent jamming, but he did this to speed up typing, not slow it down. He was, after all, in an economic death struggle with competing inventors, and while his approach was more intuitive and experimental than Dvorak’s, modern analysis shows that he actually developed a remarkably good layout by the three measurse we now know to be important:

- Balancing workload between the hands

- Maximizing load on the home row

- Frequency of hand alternation during actual typing (to permit one hand to prepare to type while the other is pressing a key.

According to Norman and Rumelhart, although the Dvorak layout is superior in the first two regards, QWERTY excels at the latter, and the effect is essentially a wash.

So how did the myth arise? Mostly from Dvorak himself, who like anyone acting on a sincere belief that his reasoning must be correct even if it contradicts the facts, stretched the truth more than a little. Then there was the Associated Press report of a US Navy study in which novices using the Dvorak keyboard “zipped along at 180 words a minute.” Only it didn’t happen, and the Navy Department, in an October 1, 1943 letter to the author said it had never conducted any such study. (Foulke, 1961). Apparently, the AP had transposed the “8” and the “0.”

The navy had in fact conducted a study; they just didn’t find the spectacular results that the press like to pick up and amplify, and that Dvorak himself was keen to see. In fact, the navy study was deeply flawed, and really only measured “the Hawthorn effect.” This term stems from ergonomic studies at a Michigan auto factory early in the century that found surprising performance improvement when experimental changes were made on an assembly line—and then more improvements when the changes were reverted. The researchers finally realized the obvious: workers speed up when they are being watched. They also speed up when they are taken away from their normal work environment and told their speed is being measured, as was the case in the navy study.

So forget the navy study. It’s rubbish. In 1956, though, Earle Strong conducted a careful scientific study of typing for the US General Service Administration. He found that expert typists took 23 days of Dvorak training to match their previous speed on the QWERTY layout. They then continued to train alongside an equal number of QWERTY typists, and were unable to keep up. That is, in direct, head-to head competition between highly skilled and motivated typists, the QWERTY team outpaced the Dvorak team, and Strong was forced to conclude that there would be no value to the government in retraining its workforce.

Typewriting sprints on both QWERTY and Dvorak layouts have exceeded 210 wpm and have been so close over the years that no conclusion can be drawn.The fastest sustained typing (over 50 minutes) ever recorded remains 150 wpm by Barbara Blackburn using the Dvorak layout, however, given that Dvorak typists usually take it up under the expectation that its myth is true–and therefore are clearly over-represented by people intending to train for speed, it’s dubious whether we can draw any conclusions from this. Did Barb make the record books because she typed on Dvorak or because she tried really hard? In 1959, Carole Bechen typed 176 words a minute for five minutes on QWERTY, but does this prove anything either?

The record books don’t represent real world typing, and anecdotal evidence isn’t evidence at all. Here is what researchers have found:

“No alternative has shown a realistically significant advantage over the QWERTY for general purpose typing.” (Miller and Thomas, 1977 509)

“There were essentially no differences among alphabetic and random keyboards. Novices type slightly faster on the Sholes keyboard [QWERTY] probably reflecting prior experience… Experts…showed that alphabetic keyboards were between 2 and 9 percent slower than the Sholes and the Dvorak keyboard was only about 5 percent faster than the Sholes…” (Norman and Rumelhart , 1983, 45)

A large scientific study during the 1970s found that most professional typists (remember, this was the heyday of typing pools and electric typewriting) average no more than 60wpm, less than half the maximum speed attainable by anyone on any keyboard who makes a good effort. Dispatchers and certain time-critical typing jobs pushed workers to 80wpm, still easily attainable with any keyboard.

So if QWERTY is the lead weight of history, dragging us down by our fingertips, why don’t those whose jobs depend on typing come anywhere close to its limits? Simple. The real world is not a typing competition. In the real world, typists and thinking while typing, and they just don’t need (or can’t sustain the mental effort) to put words down any faster.

In the end, Dvorak is a fine tool, well engineered, and might well be ever so slightly superior, but it just doesn’t make any difference. A $10,000 racing bike is a superior tool to my Schwinn, but unless I decide to train for the Olympics, it’s a pretty meaningless distinction.

Having presented all this, I must confess that I’ve never given Dvorak a first hand try. I taught myself to touch-type using an Apple IIe program of my own design, based on a one-page magazine article. Since then, I’ve never found typing speed to be a constraint, though I really only type up to about 50wpm. I’ve always felt that learning Dvorak is one of those things that, like balancing your checkbook in hexidecimal, you could learn all right, but at a cost to your sanity and ability to function in the real world.

But what do you think? What is your experience? Do you have studies I haven’t mentioned? Anecdotal evidence you’d like to share? Leave a comment. Send this to your Dvorak typist friend. Let them leave a note. I’m interested to know what you think.

And if you like science fiction and fantasy, pop over to my newsletter signup page for a free, signed e-sampler of award-winning stories.

Foulke, A. (1961) Mr. Typewriter. A Biography of Christopher Latham Sholes, Boston, Christopher Publishing.

Strong, E.P. (1956) A Comparative Experiment in Simplified Keyboard Retraining and Standard Keyboard Supplementary Training, Washington D.C., US Government General Services Administration

Miller, L.A., and Thomas, J.C. (1977). “Behavioral Issues in the use of Interactive Systems”, International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 9,509-536.

Norman, D.A. and Rumelhat, D.E. (1983) “Studies of Typing from the LNR Research Group,” in Cooper W.E. (ed.), Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting, New York: Springer-Verlag.

I love this post! I have touch typed QWERTY since before you were born and what strangles me is having to thumb type on my ‘phone.

A word about typists who think while typing. Without statistics, I hazard that the majority of touch typists do not think much—at least about what they’re typing—while dancing on the keys; there is now usually time to edit afterward. A case historical case in point is that, when my engineer grandfather was asked to go to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in the 1940s to build housing for the workers and families who moved to the Secret City to work on the Manhattan Project, my grandmother accompanied him and worked in the typing pool. Because the information was classified, each typist was require to add a cryptic note at the end of each document. Gran’s was lbc:tbnr. That was her initials followed by the initialism for “typed but not read”, indicating she had put her mind in neutral and just let the letters from the notes she was given flow onto the typing paper without having left a conscious impression in her mind.

I will be sharing this and hope you hear from a few rabid human word processors.

I’m practically a Dvorak evangelist, though rather a quiet one who’s never really tried and never made any converts. So maybe not an evangelist, but still personally went up from 60-65 wpm on Qwerty to 70-75 on Dvorak.

I learned with a printed “cheat sheet” and my Qwerty keys in place so that I could get on others’ computers and other people on mine. 3-4 weeks to learn, and the first week at 10 wpm! So a painful start, but at least for me worth it.

But I tried to get my top Qwerty students to try Dvorak “for fun,” which didn’t really go too far, and my friends just keep telling me, “I should learn that some day.” And honestly, that is fine.

To dcwritesmore I do add that I’m agreed that NO ten-finger system is really right for phones or devices, which is why we made Modality Typing System, but that’s a different topic.

But for the topic at hand, my personal opinion and experience is that Dvorak really is better, Colemak probably better than that, Qwerty the worst in certain senses. But truly, Qwerty really is a solid system, and, as our host has said, “Good enough.” Which is just fine for most, which is why I don’t really go around pushing Dvorak.

Keep in mind also that the Navy study was conducted by one Lt. Dvorak.

Yes, THAT Dvorak.

I think words per minute is a less useful measure than sustained pages per hour. In 1982, I could type 5-6 pages per hour for 12 hours straight (using my 2-and-a-fraction-finger “method”). That might only average 25 wpm, but I still got jobs done much faster than did “faster” and better trained typists, because they could never maintain their rates.

I’m practically a Dvorak evangelist, though a rather quiet one who’s never made a convert or even really tried that hard. So maybe not an evangelist at all, though I do testify that my Qwerty speed of 60-65 wpm went up to 70-75 with Dvorak. I know that’s not always the case, but for me it was worth it.

It took me about a month to learn, and I kept my Qwerty keys in place and learned by a cheat sheet so that I could go to other computers or other people could use mine.

To dcwritesmore, I do add that devices is a completely different animal (one thumb, not ten fingers), which is why we developed Modality, but for me on physical keyboards, I will always go Dvorak unless perhaps I switch again to Colemak.

The other switch I could potentially make is one of those ergonomic boards that Mr. Hardwick describes elsewhere, though they are expensive and bulky and not very practical for the traveling business man. So I’m not sure on that one…

In the end, though, I do agree: for most people on the physical keyboard, Qwerty really is quite a solid system and certainly “good enough.”

Keeping all Navy studies and other articles aside, the real advantage that Dvorak has over QWERTY is comfort. I can say that easily after my first hand experience using all of the big three… I’ve documented my journey in the articles below.

https://julxrp.wordpress.com/2012/11/21/colemak-vs-dvorak/

https://julxrp.wordpress.com/2014/01/28/your-keyboard-you-ill-stick-with-colemak/

https://julxrp.wordpress.com/2014/08/25/good-bye-colemak-its-been-fun/

Having tasted the comfort of the alternative layouts, I am struggling to love QWERTY layout. But I choose to QWERTY right now because I am looking to be universally proficient.

If you are going to be using just your own system and you do not mind having a bit more of a geek factor, I would really suggest the alternative layout of Dvorak or Colemak.

Out of the two, the only advantage that Colemak has over Dvorak is the shortcuts. Otherwise they are pretty much identical. There are those who do not like the way that Dvorak works the right pinky with the letter ‘l’, but that is small and subjective.

When I was young, I made computer programs in my free time. When I got a job programming, I typed on the job and late into the evening at home. I seldom looked at the keys and used shortcuts to move focus, never the mouse.

I recall watching my fingers finish typing out the “paragraph” of code that I was making. On the QWERTY keyboard, my hands were hovering over the keys moving in opposing circles in order to reach the “seldom typed” letters. Computer code naming simply goes all over the place. I switched to DVORAK and now my hands stay over the home row.

One of the things that got me started in thinking about switching back to QWERTY was this

http://allthingsergo.com/blog/articles/colemak-dvorak/

All things considered, I took the plunge and returned to QWERTY because of it.