A day ago, a fire drill led me to post the following:

No matter what your building says, the data says most fire fatalities occur because of delay, not evacuation route.

Those who move early, by whatever path is still working, survive.

I was annoyed because my building has instituted an interlock that disables the elevators once the fire alarm goes off. I understand why, but the reason has more to do with managing herd behavior and liability than wisdom–and from the perspective of a smart, fit person who wants to survive, it’s simply the wrong thing to do. Disabling the elevator is a change made after the 911 attacks, and reports that some people in the Twin Towers died when the elevators they were riding in stopped on or became disabled on burning or smoke filled floors. That’s horrific, but the fact is, we do not know how many people that actually happened to, but we DO know that hundreds, probably thousands, escaped in working elevators while systems were still functioning. And that many who died were trapped in the building because of disabilities that made flight down the stairs infeasible. The sum of global experience tells us this is the rule. Typically, in any kind of high rise disaster but especially fire, those who get out quickest are most likely to survive, while those who wait like they are told are–should the worst happened–likely to be trapped and doomed.

I also posted this:

In 1988, 165 of 226 men aboard the Piper Alpha platform died waiting in quarters or at muster stations for help or orders that never came since communications were down.

All survivors ignored procedure and escaped however they could.

Be a survivor.

The lesson is clear. When the fire alarm goes off, get out of the building immediately by the quickest, surest, route–and in many cases that’s going to be the elevator, which is why modern building codes now require hardened, fire-resistant, pressurized shafts and lift cars with independent power. I don’t work in such a building.

And as it happens, my building just caught fire. I’m literally writing this in a Starbucks across the street, which I reached through tunnels after getting my ass out of the building. Here’s how it went down and what we all can learn from it:

- I had just arrived, logged in, put my phone on the charger, and walked to the break room for coffee when the lights started flashing. I was leaning around the coffee maker to reach the spigot and though the overheads lights were bad. A few seconds later, as I was moving to get the creamer, the alarm sounded.

- I immediately stopped what I was doing, walked back across the floor to my desk, logged out, and grabbed my bag–the little bag in which I carry this laptop. This was a mistake.

- By the time I returned to the central hallway where the elevators and stairs are, dozens of people were already crowding in–as per official procedire. I walked past directors, managers, and peers without a word and slipped into the nearest stairwell. This was likely another drill or someone’s burnt popcorn, but in case it wasn’t, I didn’t want to waste time on discussion, chit-chat or challenge with twenty floors below me. This was smart.

- It turns out, this was a real fire (as I write this line, fire trucks are pulling up) and a department was already evacuating into the stairwell two flights down. The stairs in our building are narrow, so I joined the ranks and climbed down with them, trying only to keep up and help everyone stay safe. We climbed down several floors, then they all exited onto another floor. I’m not going to say that was a mistake, but…

- I kept going. As it happens, I had climbed down the full 17 floors (about 21-22 floors in height) during the fire drill, so I knew I could do it safely and quickly, that I would not become trapped behind any locked doors, and on the other hand, that I definitely would become trapped if the building authorities called for a more general evacuation into the undersized stairs ahead.

- I continued down at a rapid but safe pace, exited into the basement, stopped in the restroom, walked through the largely empty tunnels, and emerged here, where I walked over to see the general evacuation I had fear just starting with a trickle of employees out onto the sidewalks.

I’m sure everything will be fine for all those who followed procedure, but I stand by my actions. The only things I did wrong were A) leaving my phone at my desk and walking away, and B) going back for this computer. I should have set my coffee down where I stood and headed for the elevator. Had I got in it, it would have carried me down even if disabled by the alarm. Had it been locked out before I reached it, I could have been in the stairwell ahead of anyone else. Don’t get me wrong. I would stop and help others if I was needed–say in a plane crash or if trapped together. But I knew people who died in the 911 attacks. I know people who survived. They’ll tell you the same thing I’m telling you here: job one is not to become trapped in the first place.

Everything’s fine. I’m headed back to work. Stay safe.

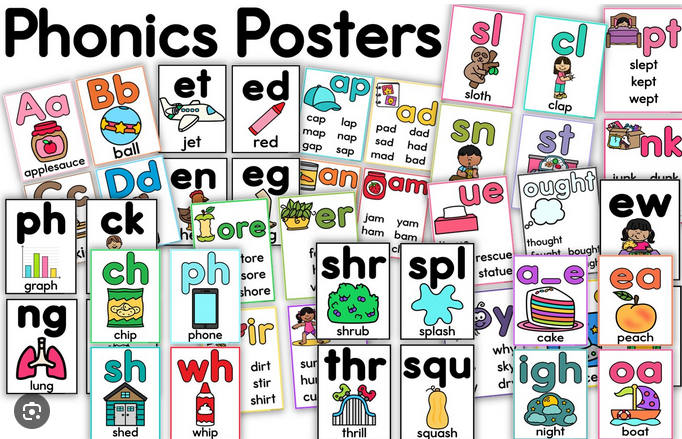

Then, they practice “sounding out” words by breaking them down into these sounds and blending them together to read the word. For example, they learn that “c” makes a /k/ sound, “a” makes an /a/ sound, and “t” makes a /t/ sound. Putting these together, they get the word “cat.”

Then, they practice “sounding out” words by breaking them down into these sounds and blending them together to read the word. For example, they learn that “c” makes a /k/ sound, “a” makes an /a/ sound, and “t” makes a /t/ sound. Putting these together, they get the word “cat.”

because of trees downed across lines strung along a heavily wooded and somewhat overgrown road. Houstonians love their trees (I do too) and with the weather this close to the gulf, the generator I installed last summer has already been pressed into service five times, including the May 16 derecho that also left a million people in the dark. But Beryl was the first prolonged outage that forced us to really put the new emergency power system to the test, and so I thought it appropriate to post a little report, in case anyone cares to learn from my experience.

because of trees downed across lines strung along a heavily wooded and somewhat overgrown road. Houstonians love their trees (I do too) and with the weather this close to the gulf, the generator I installed last summer has already been pressed into service five times, including the May 16 derecho that also left a million people in the dark. But Beryl was the first prolonged outage that forced us to really put the new emergency power system to the test, and so I thought it appropriate to post a little report, in case anyone cares to learn from my experience.