When I started writing seriously back in 2011, I knew the last thing I needed was to start coming home every day from my corporate desk job and spend hours more behind a desk, so instead I learned my craft standing in the bedroom, typing on a little Acer Netbook perched high atop a tall chest of drawers. That worked well enough

When I started writing seriously back in 2011, I knew the last thing I needed was to start coming home every day from my corporate desk job and spend hours more behind a desk, so instead I learned my craft standing in the bedroom, typing on a little Acer Netbook perched high atop a tall chest of drawers. That worked well enough

In eight short Cold War years, the USA went from second fiddle in space to The Nation That Put Man On The Moon. How?

The Americans were smart, loved their country, and had good German rocket scientists. The Soviets were smart, loved their country, and had good German rocket scientists. So what happened?

Moon hoax conspiracultists are an odd bunch. They invest endless energies making and parroting Internet claims about complex topics they don’t understand, but none at all investigating the actual world they live in.

A case in point is the fairly recent claim that images like this “prove the hoax” by showing “film crew credits for those filming the Apollo missions”:

Today, March 3rd, 2019, everything changed. It might be just another spring day wherever you are, but this is the day the space age got back on track.

Bold statement? Allow me to back it up.

Nearly everything most people alive today think about NASA is based on the Apollo program and NASA’s high-profile attempts to keep the manned space program going through the Congressional withdrawal from its economic aftermath. The moon landings were a wondrous achievement and the Space Shuttle accomplished much, but the fact is, NASA was not founded to go to the moon or run an expensive orbiter program for three decades. NASA was created to continue The N.A.C.A.’s work of fostering and promoting American industry–to continue its legacy of aeronautical research and advancement into the space age.

While the Apollo program and Space Shuttle contributed to this goal, they were also expensive (though necessary) distractions from the entrepreneurial thinking needed to get from “One Giant Leap” to meaningful movement beyond the Earth. But now, after two decades of competitions patterned somewhat after the aeronautical Guggenheim prizes of the 1920s and 30s and administered by NASA, space entrepreneurship is booming.

In the past, firms bid on military style cost-plus contracts to sell NASA the boosters it needed. Now, Space-X (and others) are developing their own boosters with NASA as collaborator and customer for for-profit launch services. It can hardly be a surprise then, that Space-X is “boldly going” to innovate and cut costs. The cheaper they fly, the more they bank.

And so, this morning, the first privately owned crew launch system in the history of Earth docked with the ISS, without berthing by robotic arm and without manual intervention by rocket jock astronauts. It was only a test flight, but it was far more than a step toward America’s return to space following the retirement of the shuttle. It’s a sea change. It’s the beginning of space, the industrial marketplace.

It changes everything.

I am often asked about the claim that NASA lost the original recordings of video shot during the moon landing. This idea is frequently breathed new life either my moon hoax conspiracultists suggesting it as proof that we never went, or by those wishing to argue that government can’t get anything right.

It’s true, too–sort of. The original master recordings of the TV footage shot on the moon are lost, as far as is known. But surprise, surprise, the actual facts don’t remotely support either either argument.

In the mid 1960’s when we were preparing for the moon landings, most TV cameras weighed about 300 pounds (plus associated equipment). Early portable cameras might weigh 80, and require a backpack for power and electronics, and drew three or four hundred watts.

Mind you, this was not to record anything, this was just to take the picture and radio it back to the station for live broadcast.

These cameras were far too heavy, and used far too much power for NASA, which had already designed the spacecraft systems and simply didn’t have room or power to transmit TV back to Earth at the normal 525 lines of resolution and 30 (interlaced) frames per second used in the US.

So NASA contracted with RCA and Westinghouse to design cameras more suitable with the space program. They ended up with several, each based on brand new and clever but cutting edge technology. These “Apollo TV Cameras” weighed in at under 8 pounds and seven watts, absolutely remarkable for the day, but they captured a 320 line picture at only 10 frames per second, and sent it back to Earth as raw, analog data.

On Earth, that data could only be decoded on a dedicated machine, built by Westinghouse, and the technology did not yet exist to convert and analog TV signal from one format to another, so it could not be converted to the NTSC standard used in America, much less to any of the other hundreds of broadcast standards in use around the world.

To get around this, RCA built a special console in which the Apollo TV Camera signal was displayed on a specially made, slow phosphor screen inside a dark housing, where a standard TK-22 camera filmed in using the NTSC standard.

This was a cool machine for the time. Among other things, it had an early hard disk used to store analog video frames in real time, and it had a special circuit to help stretch those frames to fit the NTSC standard—but effectively reducing the 320 line image to 262.5 lines!

That was considered okay though, because that was comparable to the old kinescope system used to archive TV on film, so it was considered good enough.

The signal was recorded twice. The raw, unprocessed signal was recorded along with all the other spacecraft telemetry and DCE messages straight from the antenna. The NTSC signal was recorded on a stock Ampex VR-660B video recorder.

Both these measures were safeguards against failure of the microwave circuit back to Houston. Neither was considered of value once the footage aired. People just didn’t think that way back then. TV was for real time. Film was for journalism.

Videotaping was still in its infancy and was not widely available. It was used mostly to save prerecorded programming until it’s schedules air times (in different time zones) and until mid-season reruns. Then it was usually written over, because the tapes were very expensive, and there was no way to compress the data. Keep in mind, there are probably a hundred homes in my neighborhood that contain more stored video than all the vaults of all the networks in the world in 1969, and at much higher resolution.

Years later, some of the operators who had worked at the Deep Space Network stations saw how ratty the archival network footage was and started thinking about what they’d seen on their monitors at the time. They realized the the original, 320 line data was recorded on tape—not on video tape but on the raw data tapes, before going through the machine and before all the subsequent interference. But by then, the Apollo program was over, the equipment was obsolete, and archived data had been moved and moved again over the years.

If we had those data tapes today, we could recover the 320 line video broadcast from the moon, and it would look something like this photograph taken of the converter screen at the time:

That would be cool, even though the cameras had a host of faults that introduced ghosting and artifacts even before the signal left the camera. That data might still be in a warehouse, or it might be in the garage of some technician who “saved it” and then died before telling anyone about it. Or it might be lost.

If I recall correctly, NASA closed the data analysis office that processed Apollo telemetry data years ago, but volunteers saved the necessary equipment to read the old tapes. In fact, a paper was just released announcing that this effort recovered a critical section of previously lost data from the Apollo Lunar Science Experiments left operating on the moon until the mid-1970s. And that’s awesome—but it’s also very possible that that data might have been written over the older data from the landings.

So yeah, NASA recorded over or lost master tapes of an historic event that had done the job they were capture for and were recorded in a bespoke format that could only be read by antiquated, one-off machinery. Anyone who’s ever worked in a an actual government office can tell you stories of similar bureaucratic penny pinching, but yeah, in this age of nearly free, nearly perfect digital storage, you can be excused for finding this a tad short sighted.

But you know what else was short sighted? In the early 1960s, RCA Victor decided to demolish the Camden, New Jersey warehouse housing four floors of audio masters, many of them wax and metal disc recordings, test pressings, lacquer discs, matrix ledgers, and rehearsal recordings. Out of all of that, RCA saved a set of recordings by the (then famous) Enrico Caruso, but that was it. Shortly before the building came down, some collectors were permitted to enter the building and salvage whatever they could carry for their personal collections. Then the building was dynamited, bulldozed, pushed into the river and used as fill for a new pier.

And in 1973, when RCA decided to remaster its Rachmaninoff recordings to mark the composer’s centennial and capitalize on the growing high fidelity audio market, they had to buy them back from private collectors. Today, the wax and other obsolete recordings could be remastered using laser scanners and computer signal processing to produce reproductions far better than the originals–but they are landfill. Obviously, RCA never really had a record business, and you can’t trust private enterprise to make a buck, right?

An Internet denizen asks how the moon’s axis and orbit combine to affect how we see the moon, and the answer is far more delightful than you might imagine.

For purposes of understanding why we can only view one side of the moon from any point on Earth, you can assume that both have the same axis of rotation (they don’t, but we’ll come back to that) and that you are looking down on the north pole of both Earth and moon:

An Internet denizen asks:

Q: How were we able to put a man on the moon with the level of technology that was available in 1969?

The answer? By spending a crap ton of money over ten years, peaking at 5% of the federal budget. And by relying as much at possible on already proven technology, which isn’t as “high-tech” as you think (more on that below).

Q: Did NASA have advanced technologies that were just not made public?

Very little. They developed the advanced technologies they needed, and except where they were borrowing from the military, they then made them public. NASA’s primary job, after all, is to promote and nurture the American aerospace industry.

Here are a few examples of how the technology came to be:

- Back in 1961, NASA knew it would need a big moon rocket, but they didn’t know how big or have a design for it. They knew, however, that back in 1955, Rocketdyne had started work on the granddaddy of rocket engines for the Air Force. The first attempt (the E-1) had been a dead end, but the second try (the F-1) had been successfully fired in 1957—the year before NASA was founded. The Air Force had abandoned the engine, but NASA paid Rocketdyne to continue development, and the engine was improved continually throughout the Apollo program, including thrust and reliability upgrades from one mission to another. For all that, the F-1 was in many ways a crude engine by today’s standards. In particular, it required hundreds of difficult, manual welds in refractory metal, which all had to be perfect. Today, the same engine could be formed in three (principle) pieces and welded together by robots, but back then, it was all done by hand.

A while back, a reader of my moon hoax debunkery asked who started the hoax idea rolling in the first place.

Naturally, at the time of the Apollo Program, some folks didn’t believe it, just as many people don’t believe anything they ought to or do believe what they shouldn’t. I had a high school teacher who didn’t believe in the Titanic because “nothing that big could float” (never mind the fact that by the time I was in high school, about a third of all ships on the oceans were larger than the Titanic).

One of my favorite moments from the entire Star Trek franchise occurs in the Next Generation episode, “Hide and Q” when Captain Piccard quotes Hamlet, saying,

“What he might said with irony, I say with conviction. What a piece of work is man. How noble in reason. How infinite in faculty. In form, in moving, how express and admirable. In action, how like an angel. In apprehension, how like a god”

As a science fiction author, I spend a lot of time exploring what it means to be human. I subscribe to the view that indeed, that question and questions like it are the heart and soul of the genre, and of speculative fiction in general.

What then does it mean to be human?

There are many answers to this question, of course, and not all particularly flattering, but two news items this week go a long way toward bracketing the topic.

This week, NASA launched the Parker solar probe, a spacecraft that will not only study the sun, it will dip down and sample its atmosphere.

There is a lot that can be said about this, but just think–we, puny naked apes that we are, have sent a tool to touch the sun. I’m willing to bet that, put in those terms, that thought puts a little energy in your heartbeat. Why? By completion, the Parker Solar probe mission will cost enough to foot the entire cost of all charity medical care in the US for a year (which honestly, is a much smaller amount than it ought to be). So why not, as social liberals sometimes ask (as Jesse Jackson asked about the moon landing) spend that money on the tired, the poor, the huddled masses?

There are two answers to this question, but to explore them, let’s cast our gaze back as ways–way back–to prehistory–to the Pleistocene and the beings who came before us.

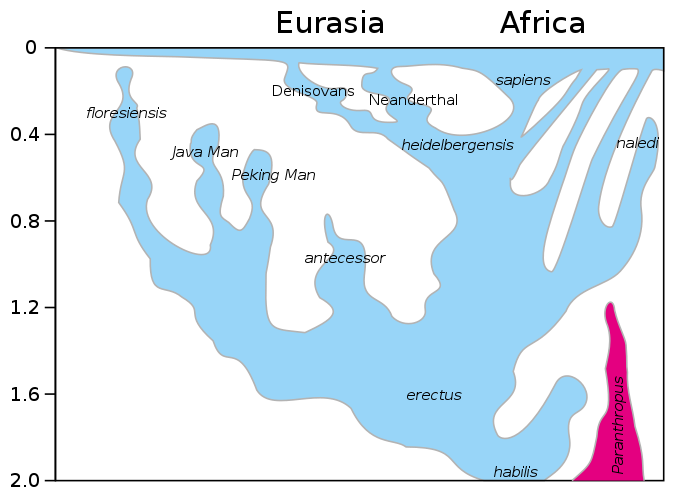

Apes are fragile, and our fossil record is spotty, but we’ve identified several dozen “missing-links” between ourselves and our nearest ape cousins. Through most of the last 6 million years, our ancestors lived in the habitat they evolved in–like any other animal. Australopithecines walked upright and had larger brains for their body size than any ape before them–but they were more like chimpanzees than us. They can be thought of as smart chimps adapted to hiking in the heat of the African savanna, and to hiding form the big cats who preyed on them. By a little little less than 2 million years ago, these early hominids had become a lot smarter, and had adapted to the use of stone tools and fire. These were Homo erectus, and they became the most successful ape that had ever lived, spreading across Africa and into Europe and Asia.

This geographic dispersion, however, took forever. A modern human in good shape can easily hike ten miles in a day. A family living in North Africa, moving camp by a mere 30 miles per year, could reach China in 150 years. Erectus took at least a thousand times that long, and they didn’t even stop at Euro-Disneyland. You might reasonably ask what reason they had to move–and fair enough except, put yourself in those shoes. Can you imagine living in any human settlement where no one takes off to start a new settlement for hundreds of years? Hell, we’d do it just out of boredom, or cussedness, or to get away from the in-laws–or to see what’s beyond the next rise.

Dr Ceri Shipton, et. al. of the Australian National University School of Culture, History and Language have been studying H. erectus sites in the Arabian peninsula. Thay’ve found compelling evidence for what he calls ‘least-effort strategies’ for tool making and resource collection. Erectus seemed to rely on the stone at his feet even when more suitable tool making flint was available atop a nearby hill. He seemed to hang around established habitation sites even as the climate made them unlivable. Shipton like to say “erectus was too lazy for his own good.” I’d put it a little differently, erectus, like many people, may have been too lazy to do things the easy way.

By the way, erectus went extinct. Humans walked on another world after our leader said,

We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.

Cynicism aside, these are words that all humans understand, be they aeronautical engineers or petty thieves. Neanderthals used essentially the same tool making and hunting strategies for a quarter million years, I built my own treadmill desk in a weekend. Sure, I “stand on the shoulders of giants,” but those giants are also humans, they also have that human spark that drives us to invent, to explore, to seek out new worlds and see what’s there and what works. That’s what gave us bread and vaccines and that’s what gave us industrialized warfare. There two are closely related. We are more than “thinking man,” we are the scheming ape, the crafty ape, the ape of adventure and conquest. What drives us forward can also drive us closer to the brink–but we cannot go back to the jungle. We are mankind, and we much adapt ourselves and our culture to our new stature as the custodians of Earth, or we will meet the same fate as the lowliest creature–eventual, inevitable extinction.

The Parker Solar Probe will touch the sun. It will help us better understand space weather, prepare for manned explorations into deep space, protect our power grid and our communications technology, and maybe even safeguard life on Earth. That’s one reason for sending it. The other reason–the better reason–is because we can.

Earlier in the “we choose to go” speech, President Kennedy said this:

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man.

This is the heart of the matter. Yes, we should feed the poor and tend the huddled masses and we can debate till the cows come home how and to what extent we should do that. But knowledge is important too, and adventure. And when the day comes that humanity no longer looks beyond the mundane requirements of our daily bread to peek over yon horizon, well, that will be the day after the last day of the human race.

Go Boldly.