I am often asked about the claim that NASA lost the original recordings of video shot during the moon landing. This idea is frequently breathed new life either my moon hoax conspiracultists suggesting it as proof that we never went, or by those wishing to argue that government can’t get anything right.

It’s true, too–sort of. The original master recordings of the TV footage sho t on the moon are lost, as far as is known. But surprise, surprise, the actual facts don’t remotely support either either argument.

t on the moon are lost, as far as is known. But surprise, surprise, the actual facts don’t remotely support either either argument.

In the mid 1960’s when we were preparing for the moon landings, most TV cameras weighed about 300 pounds (plus associated equipment). Early portable cameras might weigh 80, and require a backpack for power and electronics, and drew three or four hundred watts.

Mind you, this was not to record anything, this was just to take the picture and radio it back to the station for live broadcast.

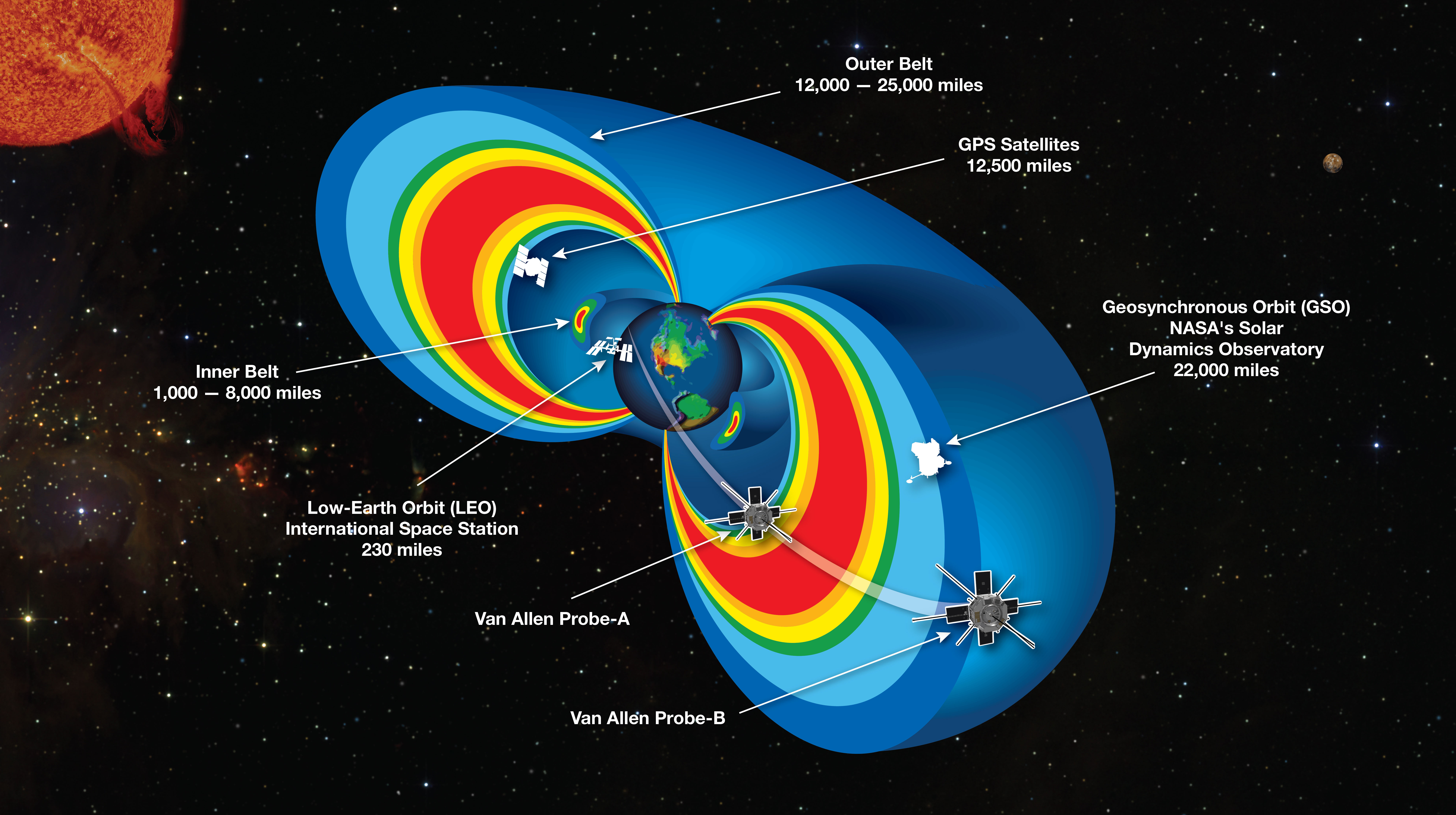

These cameras were far too heavy, and used far too much power for NASA, which had already designed the spacecraft systems and simply didn’t have room or power to transmit TV back to Earth at the normal 525 lines of resolution and 30 (interlaced) frames per second used in the US.

So NASA contracted with RCA and Westinghouse to design cameras more suitable with the space program. They ended up with several, each based on brand new and clever but cutting edge technology. These “Apollo TV Cameras” weighed in at under 8 pounds and seven watts, absolutely remarkable for the day, but they captured a 320 line picture at only 10 frames per second, and sent it back to Earth as raw, analog data.

On Earth, that data could only be decoded on a dedicated machine, built by Westinghouse, and the technology did not yet exist to convert and analog TV signal from one format to another, so it could not be converted to the NTSC standard used in America, much less to any of the other hundreds of broadcast standards in use around the world.

To get around this, RCA built a special console in which the Apollo TV Camera signal was displayed on a specially made, slow phosphor screen inside a dark housing, where a standard TK-22 camera filmed in using the NTSC standard.

This was a cool machine for the time. Among other things, it had an early hard disk used to store analog video frames in real time, and it had a special circuit to help stretch those frames to fit the NTSC standard—but effectively reducing the 320 line image to 262.5 lines!

That was considered okay though, because that was comparable to the old kinescope system used to archive TV on film, so it was considered good enough.

The signal was recorded twice. The raw, unprocessed signal was recorded along with all the other spacecraft telemetry and DCE messages straight from the antenna. The NTSC signal was recorded on a stock Ampex VR-660B video recorder.

Both these measures were safeguards against failure of the microwave circuit back to Houston. Neither was considered of value once the footage aired. People just didn’t think that way back then. TV was for real time. Film was for journalism.

Videotaping was still in its infancy and was not widely available. It was used mostly to save prerecorded programming until it’s schedules air times (in different time zones) and until mid-season reruns. Then it was usually written over, because the tapes were very expensive, and there was no way to compress the data. Keep in mind, there are probably a hundred homes in my neighborhood that contain more stored video than all the vaults of all the networks in the world in 1969, and at much higher resolution.

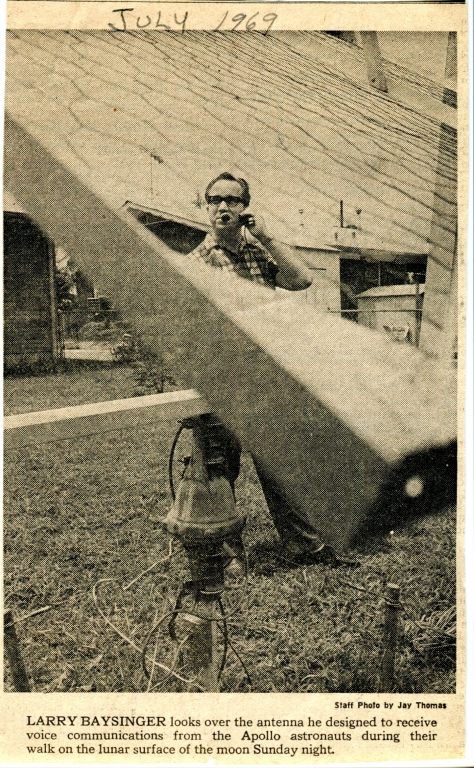

Years later, some of the operators who had worked at the Deep Space Network stations saw how ratty the archival network footage was and started thinking about what they’d seen on their monitors at the time. They realized the the original, 320 line data was recorded on tape—not on video tape but on the raw data tapes, before going through the machine and before all the subsequent interference. But by then, the Apollo program was over, the equipment was obsolete, and archived data had been moved and moved again over the years.

If we had those data tapes today, we could recover the 320 line video broadcast from the moon, and it would look something like this photograph taken of the converter screen at the time:

That would be cool, even though the cameras had a host of faults that introduced ghosting and artifacts even before the signal left the camera. That data might still be in a warehouse, or it might be in the garage of some technician who “saved it” and then died before telling anyone about it. Or it might be lost.

If I recall correctly, NASA closed the data analysis office that processed Apollo telemetry data years ago, but volunteers saved the necessary equipment to read the old tapes. In fact, a paper was just released announcing that this effort recovered a critical section of previously lost data from the Apollo Lunar Science Experiments left operating on the moon until the mid-1970s. And that’s awesome—but it’s also very possible that that data might have been written over the older data from the landings.

So yeah, NASA recorded over or lost master tapes of an historic event that had done the job they were capture for and were recorded in a bespoke format that could only be read by antiquated, one-off machinery. Anyone who’s ever worked in a an actual government office can tell you stories of similar bureaucratic penny pinching, but yeah, in this age of nearly free, nearly perfect digital storage, you can be excused for finding this a tad short sighted.

But you know what else was short sighted? In the early 1960s, RCA Victor decided to demolish the Camden, New Jersey warehouse housing four floors of audio masters, many of them wax and metal disc recordings, test pressings, lacquer discs, matrix ledgers, and rehearsal recordings. Out of all of that, RCA saved a set of recordings by the (then famous) Enrico Caruso, but that was it. Shortly before the building came down, some collectors were permitted to enter the building and salvage whatever they could carry for their personal collections. Then the building was dynamited, bulldozed, pushed into the river and used as fill for a new pier.

And in 1973, when RCA decided to remaster its Rachmaninoff recordings to mark the composer’s centennial and capitalize on the growing high fidelity audio market, they had to buy them back from private collectors. Today, the wax and other obsolete recordings could be remastered using laser scanners and computer signal processing to produce reproductions far better than the originals–but they are landfill. Obviously, RCA never really had a record business, and you can’t trust private enterprise to make a buck, right?